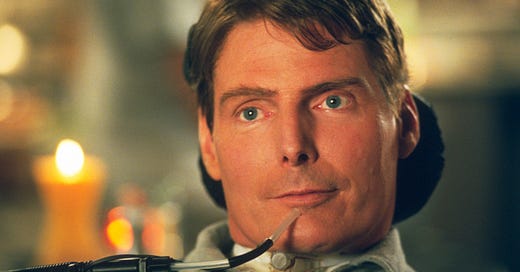

Christopher Reeve and 1998's 'Rear Window'

Didn't know there was a 'Rear Window' remake starring Christopher Reeve after he was disabled? There's a reason for that.

In honor of the 70th anniversary of Rear Window happening this week, taking this one off the paywall for everyone to read.

Up until recently, actor Christopher Reeve was the most famous disabled pers…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Film Maven to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.