Popcorn Disability: Reid Davenport's 'Life After' Is Essential

Davenport continues to show his strengths as a filmmaker with this devastating and stirring look at assisted suicide

Popcorn Disability is an on-going series based and inspired on my upcoming book exploring disability in the movies. This series looks disability-centric films and other topics related to how disability is portrayed in media and popular culture.

Casting is easy. You’ve probably heard (or read) me say this multiple times. True representation comes in opening the door for disabled directors and screenwriters to tell their stories. One director doing just that is Reid Davenport, a wheelchair user and director with cerebral palsy, whose 2022 feature I Didn’t See You There cast a harsh eye on disability representation, past and present. His follow-up film, which recently premiered at Sundance, is an ambitious and thought-provoking sophomore effort that hits on so many nuances of the disabled experience regarding medical issues and the right to life (or death).

Life After starts with the story of Elizabeth Bouvia, a California woman who, in 1983, sought the right to die in her home state. The court case kicked off a powder keg of discussion about the “quality of life” disabled people and how assisted suicide fits into that. For Davenport, his quest to find out what happened to the real Bouvia after the case takes him on a journey that shows the right to die is still something the disabled are talking about and fearing.

Life After, though, starts with Elizabeth Bouvia, a beautiful young woman struggling with extreme pain and cerebral palsy. Davenport hopes to see if Bouvia, who eventually lost her case and was medically force fed, is still alive. Bouvia’s case is fascinating as it brings up several themes Davenport explores throughout the documentary like who determines one’s quality of life, how often does medical necessity end up exacerbating disability in the name of helping, and why does society so often feel the disabled are the ones associated with laws like this?

News clips from Bouvia’s case hit on the same exact phrases — from her being “trapped in a useless body” to being described as “severely handicapped” and “tragic” — all of which illustrate to an abled viewer that Bouvia’s life is not worth living. Even when Mike Wallace sits down with Bouvia, in an interview that has not aged well, he creepily points out she’s had her hair and makeup done, because there’s no reason a pretty girl like her should look bad while wanting to die. As Davenport sits down with Bouvia’s two sisters a true portrait of Elizabeth emerges.

A bright, energetic, beautiful young woman, Bouvia believed what anyone, regardless of ability does: that if she went to college, got a good education and job, she could take care of herself. It was only once she discovered the rampant ableism in the world and the lack of access to services the disabled face that she sank into a depression so severe as to want to die.

From Jack Kevorkian to Terry Schiavo, everyone has their right to die case. But where they felt like one-off things today they are fairly common just across the U.S. border in Canada where MAiD (Medical Assistance in Dying) is now law. As Davenport’s documentary lays out, the use of MAiD in Canada, even for non-terminal cases, has jumped over the last several years, with the country outpacing other countries like Luxembourg and Belgium which have had death with dignity laws for years.

The reason for the increase is varied as Davenport shows, from doctors and patients defining unbearable pain in many ways to others, like subject Michal Kaliszan, feeling like they have no other option living in an increasingly expensive country with little support for the disabled. Kaliszan explains how once his primary caregiver, his mother, took sick it left him with 3 thoughts: “OMG, my mom’s gonna die….OMG, I’m gonna go soon after her…and OMG I need to get my shit together.” As someone who has had these EXACT same thoughts, it’s a valid concern.

The average disabled person might be able to afford themselves but if you don’t qualify for government assistance you have to pay for in-home health out of pocket, leaving many disabled people on their own. As Kaliszan explains, the lack of medical help left him looking into MAiD purely from a financial standpoint. What is the line between people utilizing MAiD purely to escape poverty, particularly if they’re disabled?

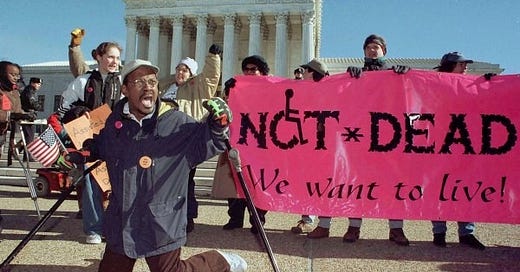

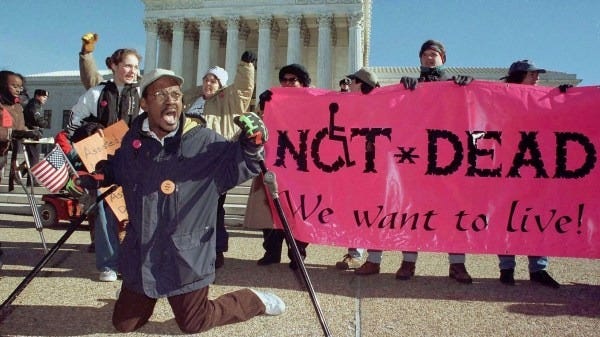

Davenport couches so many big questions, none with easy answers, into a slim 98-minute documentary. But Bouvia is never far from his thoughts, nor is the fact that very little appears to have changed since her court case. If anything, right to die laws are gaining traction, particularly in New York where Davenport shows a group of disabled protesters attempting to get any recognition when put up against a well-funded pro-death with dignity organization. If able-bodied people are determining how valuable a disabled person’s life is will we see disabled people die en masse? Are we seeing it already?

Davenport also is great documenting the little moments any disabled viewer will identify with, whether that’s watching a group of abled people crush into an elevator and refuse to make room for a wheelchair user, or a police officer interrupting Davenport while he films to ask if he’s “in distress.” These moments only illustrate the push-pull of being disabled in this country. People constantly assume we’re in trouble, but no one wants to get out of the metaphorical elevator when we actually do.

Life After is a thought provoking piece of art that should be watched by everyone, regardless of disability. Whether you think this affects you or not, all it takes is one accident (as talking head Melissa Hickson talks about with regards to her husband) to have your right to make medical decisions taken away. This movie chilled me to my core but it’s imperative you see it.

Grade: A

Life After will debut sometime in 2025.