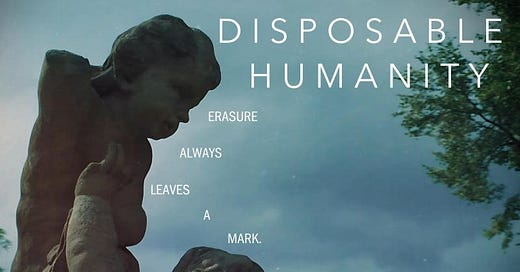

Popcorn Disability: 'Disposable Humanity' Reminds Us of History's View of Ableism

Cameron S. Mitchell's documentary takes a different look at the Holocaust

There’s a moment found within director Cameron Mitchell’s documentary Disposable Humanity where one of the talking heads mentions how the lack of input by disabled people in Holocaust memorial projects, specifically about the disabled people murdered during that time, means able-bodied people who put them together fail to understand the significance. The concept of “popcorn disability,” as I’ve defined it, is just that: the idea that movies are made for able people and can never understand the true disabled experience.

Disposable Humanity is about what implications the lack of disabled voices has on history and memory. On top of that it’s a searing, heartwrenching exploration of a part of the Holocaust that is still not discussed in-depth today because of continued stigmas against the disabled community. As we’re seeing today through programs like MAiD in Canada — read my review of Reid Davenport’s Life After — the realities of Mitchell’s documentary are alive and well.

Mitchell’s goal with his documentary is two-fold: to detail the ignored and underdiscussed euthanasia of disabled people in the lead up to the more well-known Final Solution, and explore how the continued stigma surrounding disability means the goal of memorializing it is non-existent. This stigma is represented in the movie’s first scenes, as Mitchell and his father travel through Germany to get to the various locations in the film, coming up against non-wheelchair accessible locations and transportation. Without saying it, if countries cannot even make it accessible for disabled people to travel and visit, there is no one to really check whether disabled history is being told accurately.

And that’s really where Mitchell’s documentary thrives, in the desire to detail how those with disabilities, unfortunately, were the first to be exterminated in the lead-up to the Holocaust. Mitchell’s camera glides silently through places where disabled people — who, sadly, are unnamed to this day — were brought in under the belief that they were being transferred to other places only to die. The camera captures forged death certificates, filled with information that, based on the people’s disabilities, could conceivably explain away their deaths. But the true horror isn’t exclusively found in these locations, though their power is still palpable, but in the coordinated effort, little that it took, to make their deaths okay.

One talking head details hearing his grandmother discuss her brother, who seemingly dead as an infant. When he went looking for proof of the boy’s existence he discovered his grandmother’s brother actually died as an adult. When broached with the subject again, the old woman recounted another story. Later, propaganda films are shown, filled with extremely disabled and mentally ill people, weaponizing their bodies to emphasize grotesquerie and justify that the quality of their lives wasn’t worth living. These two stories illustrate how disability remains so uncomfortable for people to discuss as to render the people who died invisible.

It’s interesting that Mitchell and Davenport’s docs are releasing now, as they are two halves of a whole, showing the historical horrors disabled people faced that are, in some ways, being mimicked today. Mitchell’s father asks a woman working at a psych hospital/memorial to respond to how it feels to have a memorial for atrocities committed against those seeking psychiatric treatment in a functioning psych hospital. Her response is that one has nothing to do with the other, that this is simply the location of where events happened. It’s no different to the belief that MAiD has nothing to do with disability or that ableism is non-existent. If we can’t have an honest conversation about disability we’re doomed to repeat the same issues.

Mitchell lays out complex topics with a clear, succinct voice and talking heads that are able to blend emotion with fact. There’s a sensitivity to the way the camera looks at images you have seen in countless Holocaust docs but, with disability, it comes off differently, maybe because disabled people come at things with more helplessness and a lack of advocacy. The talking heads all speak with such passion and fervor, understanding that even though they aren’t disabled themselves they speak for a group that remains marginalized.

Disposable Humanity is another must-see documentary in an already strong year. Mitchell tells a story that needs to be told and demands the audience to never avert their gaze.

Thanks Kristen. This is an excellent review. Two more docs to watch! We’re in the middle of a show called secrets of the dead (PBS) and this one is on a notorious Nazi art dealer Bruno Lohse. He knew the doctor (Theodor Morell) before Mengele who influenced all his “experiments” on the disabled. Horrifying. Also, did you mean died when you wrote he seemingly dead? Thought you might find that helpful.